|

Are We There Yet? Getting to Red Lake

The journey to Red Lake in the 1920's was very different than it is today. Highway 105 did not exist, the closest full service railroad station was Hudson (near Sioux Lookout), and air travel was too expensive for all but a few prospectors. At the height of the gold rush, there was a discussion about connecting Red Lake to a Canadian National Railway line. However, both the company and the provincial government decided that the short-lived gold rush would not offset the cost of connecting the remote area. Prospectors (and later mine workers) would travel to Hudson by train then make the 217 - 390 kilometre (135 - 190 mile) journey by canoe, snowshoe or dog sled. In the summer months, prospectors would load their canoes with supplies and navigate a series of northern lakes and rivers on their way to Red Lake. The men would have to portage their canoe and supplies multiple times during their journey. In the winter, gold seekers would buy or hire a dog sled team in Hudson or set off on foot. Because of the high cost of a sled team, it was not uncommon to find prospectors who had never met teaming up to split the cost. Depending on conditions, the journey to Red Lake by dog sled could be completed in seven to fourteen days. For those prospectors that could afford the expense of air travel, the journey was cut down to 144 kilometres (90 miles) and was completed in an hour. |

|

All In a Day's Work: Prospecting and Exploration

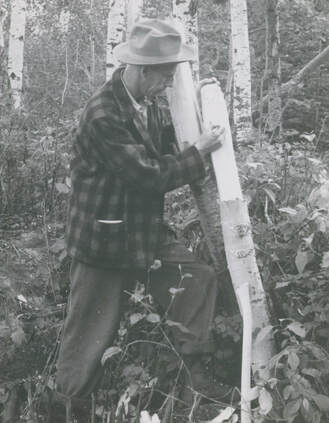

Many of the early prospectors did not have formal training in geology but were nevertheless very knowledgeable about what they needed to look for. Gold prospectors would hunt for granite outcrops with quartz veins and would examine the veins for visible gold. Before March 1926, prospectors purchased their Miner's Licence (later a Prospector's Licence) before coming to Red Lake as there was no Mining Recorder's Office in the area. With licence in hand, the prospectors would hike all over searching for signs of gold. If they found a site of interest, they would stake a claim. Each claim was marked by four posts. The prospector would stake the first post in the northeast corner then continue staking in a clockwise direction. The first post was labelled with a '1', the prospector's license and name and the date as well as a government issued metal mining tag. The remaining posts would be numbered according to their placement (2-4) and the corresponding mining tag. To be official, prospectors needed to register the claim with the regional Mining Recorder's Office. Before March 1926, this meant travelling hundreds of kilometres back to Rat Portage/Kenora. To keep their claims active, prospectors needed to work and assess their claims. In Ontario, prospectors needed to complete a minimum of 200 hours of assessment within five years or the claims would lapse and revert to the Crown. Assessment work could include but was not limited to taking samples and digging trenches. Samples were often assayed (tested) to find out the mineral value of the property. If the assay results were good, prospectors would go about securing more funding for further exploration. |

|

Prospecting and exploration was an expensive undertaking. Many prospectors were backed by large mining companies like McIntyre Porcupine Mines of Timmins, ON or syndicates made up of individual investors. Mine promoters like Jack Hammell (Howey Gold Mines), Joseph McDonough (Madsen Red Lake Gold Mines), Arthur W. White and Jack Brewis (Campbell Red Lake Mines and Dickenson Mines) were often contacted to secure exploration funding because of their connections in the industry. Promoters would make an initial investment, create a company, sell shares and often option the property to other mining companies.

The main components of exploration were trenching, diamond drilling and underground drilling. Diamond drilling, a standard method of investigation today, was expensive and limited in its reach. The steam-powered rotary drills utilized drill bits with embedded industrial grade diamonds to extract long circular pieces of rock called drill core. More often than not mining companies sank shafts and exploration happened underground because it was quicker and less expensive. |

|

The Makings of a Mine: Developing the Mine Site

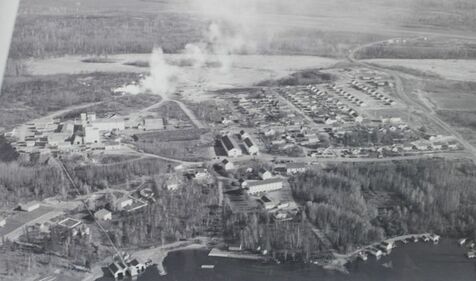

Surface development and exploration often happened simultaneously. Many of the mining projects built a surface infrastructure (warehouse, labs, steam/electric plants) before knowing if the project would be successful. Without ready access to an established town, these early mines needed to be able to do everything on site. Some of the mine sites also had gardens to help supplement the stored goods from the trading posts and general stores. Mills and subsequent facilities like clubhouses, stores and hospitals were built if exploration proved fruitful. With no roadway into the Red Lake area, mining projects had to bring supplies and equipment in the same way the prospectors came. In the warmer months, equipment was usually shipped by barge. After the lakes froze, tractor freight trains or horse sleighs were seen all along the route to Red Lake. Indigenous sled runners were often hired by the Hudson's Bay Company to transport goods from their posts to the mine sites. In 1936, the cost of shipping was $10/tonne in the summer and roughly $60/tonne in the winter. Eventually, supplies and equipment were flown into the mining camps, but it was unusual for the early gold rush period. The exception to this was when Jack Hammell borrowed planes from the provincial forestry department to bring in the Howey Gold Mines equipment in the fall of 1925. In 1936, Howey Bay was reportedly one of the busiest airports in the world, with cargo and passenger planes taking off and landing every 15 minutes. |

|

The establishment of the mining industry in Red Lake significantly affected the way of life for the local Indigenous population. Increased mining operations lead to the creation of dams and the subsequent flooding of Lac Seul, which affected the native environments. The loss of manoomin (wild rice) fields and food sources habitats changed diets and traditional ways of life. Ceremonial land was taken up by mining activity, and people were forced from their homes multiple times.

The 'opening up' of Red Lake coincided with the period when the Canadian Government was pushing the Anglicization of Canada's indigenous children. This lead to many of the children of the community being placed in two nearby Residential Schools. While the strength of the Indigenous Peoples has always been their adaptability to environmentally drive change, the profound cultural losses were exceptionally detrimental. The prospectors, miners and labourers that worked in Red Lake were from all over the world, creating a diverse workforce. Bunkhouses were often hosts of multiple different languages, with many of the new miners speaking little to no English. Inexperienced non-English speaking miners were partnered with senior miners and learned the job through observation. Indigenous men from Red Lake and the surrounding areas were employed as labourers, tree fallers, sawmill sawyers and miners. Some of the men worked full time, while others returned to their traditional hunting grounds in the winter to provide for their families. Despite the best efforts of the prospectors and mining companies, many of the Red Lake mining projects did not turn into producing mines. |

Timeline

Historic Red Lake Mining

Red Lake Geology

The Red Lake Gold Rushes

From Hudson to Headframe

Community Development

Commerce

Education

Medicine

Recreation

Mining Practices

Going Underground

Equipment

Extraction

Milling

The Mill Process

Safety

Refuge Station

Mine Rescue

Health Issues

Jobs

Contemporary Red Lake Mining

Environment

Labour

Innovation

Exploration

Indigenous Rights

Gold Prices

Mining and Exploration Companies

Goldcorp Inc.

Rubicon Minerals

Premier Gold Mines

Pure Gold Mining

Rimini Exploration & Consulting

Other Mining & Exploration Companies

Glossary